Gatekeepers

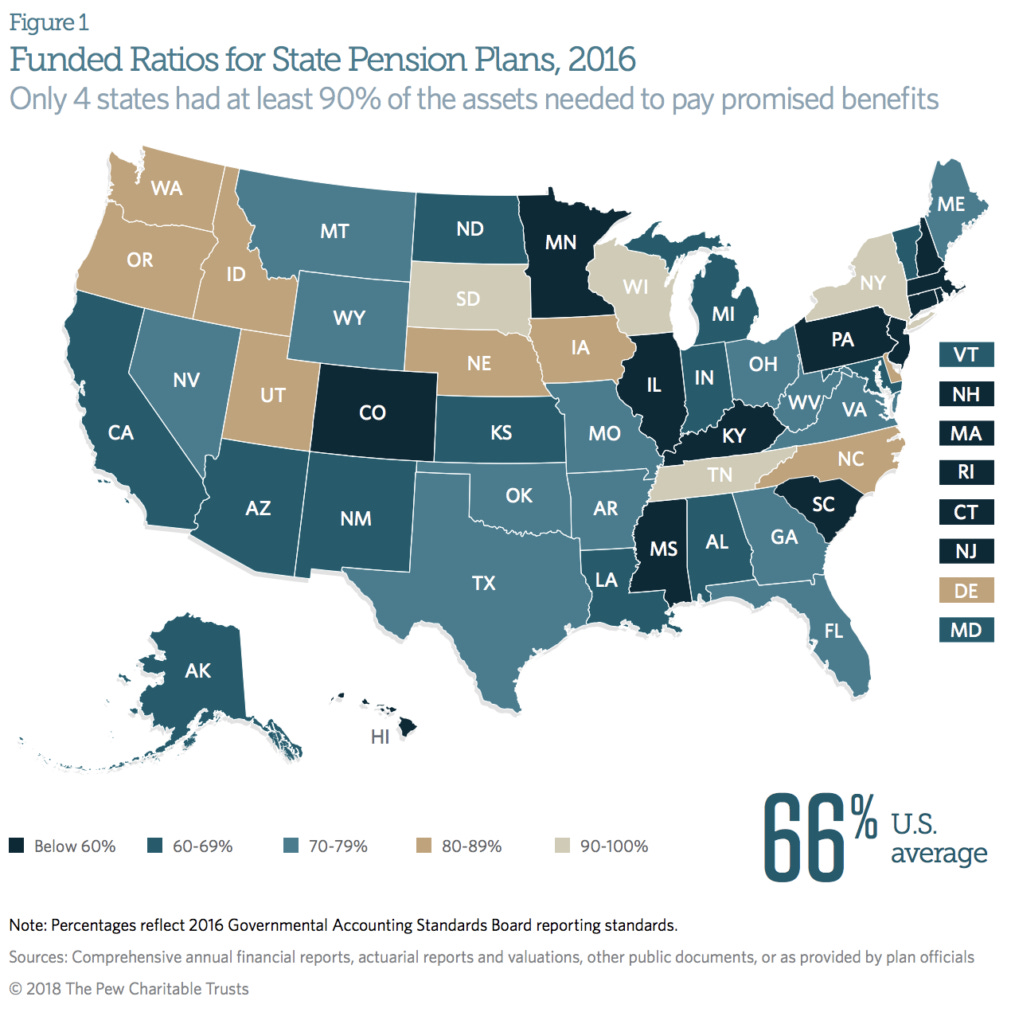

Underfunded pension obligations are a large, looming problem in almost every state in America. Decades of overpromising and underdelivering coupled with intense political pressure to kick the can down the road results in the perfect storm of burgeoning future costs. States and municipalities are using unrealistic return assumptions, but reducing these assumptions forces them to make larger contributions, a crunch on tight budgets. Attempts to reform benefits for current and future employees are met with fierce political opposition.

Perhaps there is no greater public pension horror story than that of the New Orleans Firefighters’ Pension and Relief Fund. According to the latest actuarial report from 2016, the fund has $43 million in assets for $464 million in liabilities. That’s a 10% funded ratio. The woes of the Firefighters’ Pension are numerous and include the City of New Orleans withholding payments to the Fund for multiple years.

However, the investment decisions made by the Fund’s board were unbelievably bad, perhaps borderline criminal. Mistakes include a $15 million investment in a Cayman Island hedge fund that went bankrupt, and the purchase of a failing golf course for more than $40 million that is currently valued at $1.5 million. They might as well have put cash on the table and lit it on fire.

The most recent performance report for the Fund shows $53 million of assets of which only 45% is invested in liquid securities. The remaining $29 million is allocated to hedge funds ($1.8m), private equity ($5.7m), and real estate ($20.8m). In the board’s defense, they had to sell liquid investments to fund retiree payments in recent years while the city has not made required contributions. However, even before these private investments blew up, the fund was heavily invested in illiquid assets.

I could go on and on about the terrible investment choices made by the Fund; private loans, stock in now bankrupt First NBC Bank while the bank was lending to the fund, 50% of the fund assets in private real estate. The most frightening part of this story is that the Fund’s board was working with an institutional consultant while making these decisions. Institutional consultants are supposed to be the professionals who save pension funds from making such horrible decisions.

For decades, institutional consultants have served as the gatekeepers between money managers and pension funds. No money manager is hired by an institutional client directly. First, they must pass through the due diligence of the consultant. Some of the criteria set by the consultant are prudent best practices; minimum length of track record, minimum assets under management, adequate personnel and back office capabilities.

Consultants have a bias towards expensive active managers and private, illiquid investments. After all, the investment returns are a measurement of the consultant’s work. Consultants are incentivized to try to beat benchmarks and indexes. The only way to do that is with active management. The fallacy of picking active managers is that they overwhelmingly majority of them will not outperform their benchmark net of fees. Even those that outperform will experience multi-year periods of underperformance. How long will the consultant allow a manager to underperform before recommending replacement?

In 2016, the Pew Research Center estimated the U.S. aggregate unfunded public pension liability to be $1.4 trillion. Taxpayers are on the hook, and the retirement of millions of state and local government employees is on the line. The stakes are too high to allow investment mistakes like the New Orleans Firefighter Pension and Relief Fund to repeat.

The post Gatekeepers appeared first on The Belle Curve.